I’ve written before about doctors and the arts. In 1980 the cultural historian G. S. Rousseau, citing

I’ve written before about doctors and the arts. In 1980 the cultural historian G. S. Rousseau, citing the techo-scientific nature of modern medicine, claimed that doctors no longer maintained the rich tradition of physicians as humanists. “Until recently, physicians in Western European countries received broad, liberal educations, read languages and literature, studied the arts, were good musicians and amateur painters; by virtue of their financial privilege and class prominence they interacted with statesmen and high-ranking professionals, and continued in these activities through their careers.”

Contemporary evidence contradicts Rousseau’s claim that physicians are no longer practitioners and connoisseurs of the arts. We may not personally encounter a doctor with her cello or recognize one painting en plein air in the little free time doctors have these days, but doctors write books that ascend the best-seller list, and many more write thoughtful, provocative blog posts. The poetry of doctors is published in medical journals and is available online in modest chapbooks. Nearly every major city throughout the world has an orchestra staffed by the medical profession. And the American Physicians Art Association encourages and assists physicians with art organizations and exhibits.

Is a liberal arts education valuable to physicians?

I have many unanswered questions about doctors as practitioners of the arts. I’d particularly like to know if the long-standing tradition of physicians as humanists has changed over the past half century. Higher education has definitely changed since the mid-20th century. In particular, there’s less emphasis on the value of a liberal arts education. (On this, see the excellent book, Not For Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, by Martha Nussbaum.) Has this affected physicians, either in their satisfaction with their careers or in their understanding of patients?

Although there are certainly many exceptions, it’s generally assumed that those who appreciate and/or practice the arts have a liberal education, an upper-middle class background, or both. Were pre-med students in the past more likely to study liberal arts because this was required as part of the civilizing process of higher education? Are undergraduate students today encouraged to focus prematurely on the professional subject matter of their choice? Have the prerequisites for medical school changed so as to encourage an early focus on scientific depth at the expense of a broader understanding of the humanities? How has the socio-economic class of medical students changed over the past half century and what difference has this made?

Then there is the larger question: How valuable is a liberal arts education to a doctor, anyway – an education that includes the study of literature, history, philosophy, political science, languages? I don’t have answers to any of these questions at the moment. I’m in the process of collecting data, bibliographic references, and subjective impressions.

Observing patients in the context of their lives

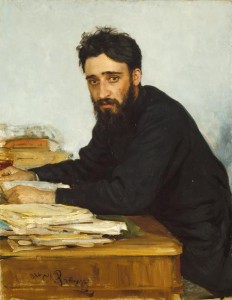

Consider, for example, the value for a physician of contemplating a work of art. Here is a portrait of Vsevolod Mikhailovich Garshin by the Ukranian painter, Ilya Efimovich Repin. If you enlarge the image and imagine a doctor taking in this human being as a patient, what is there to see? A commentary on the painting points out the rounded shoulders and upper spine, characteristic of a novelist and playwright who spends his time among books and papers. A man who seems not to care about what he wears or about the material concerns of life. Also a man who suffers from depression; whose father and brother committed suicide. Four years after this portrait was painted, Garshin fell down a flight of stairs. On purpose.

Consider, for example, the value for a physician of contemplating a work of art. Here is a portrait of Vsevolod Mikhailovich Garshin by the Ukranian painter, Ilya Efimovich Repin. If you enlarge the image and imagine a doctor taking in this human being as a patient, what is there to see? A commentary on the painting points out the rounded shoulders and upper spine, characteristic of a novelist and playwright who spends his time among books and papers. A man who seems not to care about what he wears or about the material concerns of life. Also a man who suffers from depression; whose father and brother committed suicide. Four years after this portrait was painted, Garshin fell down a flight of stairs. On purpose.

Or consider John Singer Sargeant’s “Portrait of Dorothy,” painted in 1900.  The painting reminds us that our attitude towards childhood itself can change. We no longer dress children in oversized, ostentatious clothing to make them look cute and vulnerable for their portrait, for example.

The painting reminds us that our attitude towards childhood itself can change. We no longer dress children in oversized, ostentatious clothing to make them look cute and vulnerable for their portrait, for example.

Prior to the turn of the 20th century, children had been thought of as little more than miniature adults. In the new attitude that emerged, children were regarded as individuals with a right to be healthy and happy as children. They acquired a new status in society. Pediatrics was not recognized as a certified specialty until the 1930s (in the US), but general practitioners at the turn of the century took a greater interest in the health concerns specific to children. Believe it or not, the marketing of goods to children also increased at this time. (I guess we shouldn’t be too surprised.)

Medicine is the practice of healing the whole human being

The relevance of fine art to medicine is not limited to portraits. Some of the parallels between art and medicine have been described by M. Therese Southgate, who points out that both art and medicine are about seeing – not only the superficial observation of what the eye can capture, but the deeper seeing that happens when a physician “attends” to a patient. A good physician uses her experience and intuition to see more than just another patient with high blood pressure or diabetes. “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” (William Osler)

Literature, fine art, poetry, music – they all serve to remind overworked clinicians that they are part of a timeless tradition of healing whole human beings – individuals who present themselves in all their magnificence and complexity. Also, that physicians themselves participate in the tradition of physicians as humanists. Perhaps that’s why a liberal arts education – in my opinion – makes an important contribution to the practice of medicine today.

Related links:

The physician as humanist

Marcus Welby vs. the specialists

Ich Habe Genug on Thanksgiving

My limbs are made glorious

This is a fascinating topic. I believe that current thinking can sometimes debase the relationship between doctor and patient in various ways. Governments increasingly require GPs to lecture people on their habits and treat them more like errant pupils than fully-fledged adults. My own GP, on the other hand, who recently retired, is a wonderful doctor and humanist. She respected my views, listened to my concerns, provided sensible advice and became a good friend. I think the liberal arts have an important role to play in a job which requires such involvement with other human beings. I just hope I’m as lucky next time. Thanks for a wonderful, thought-provoking post.

Thanks for your comment, Kate. You know how much you and I agree on the subject of using guilt to motivate behavior change in the alleged interests of health. Sounds like you had an ideal GP. There are many. Unfortunately for us, all good doctors get to retire.

Did you see the comment from a fellow Canadian to your “delightful post,” “A sound mind in a disintegrating body” (http://bit.ly/m1EJW4)?